When Seth and I returned to Maine last month for the first time in six years, our sense of homecoming included not just the actual home we stayed in, but the place itself: the woods, the winding roads, the people, the places we would go. And though we only got to the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Community once while we were there, that place, which the Shakers call Chosen Land, will always be a place that is somehow home, too.

My first summer internship at the Shaker Press was in 1996. I remember arriving there my first day, completely unsure of what to expect. Brother Arnold Hadd and I had exchanged a couple of letters and the Community agreed that I could come work there on a book project for the summer, but that was about it, save for deciding our subject matter: We would make a book about Deacon James Holmes, the first printer there at Chosen Land. I arrived in early June, fresh from Alabama where I had been living since the winter before, to a land where the burgeoning summer was still a bit unsteady on its feet. I met Brother Arnold; he showed me the print shop: it was in the old dairy cellar of the brick Dwelling House, and it held a Vandercook press that he only used as an imposing stone, a Golding Jobber press that would prove to be the workhorse of our project, and some type cabinets. The type was mostly Bulmer (a close relative of Baskerville) and an odd Victorian font called Graybar. There were other decorative fonts in slanted cases, and there was some wood type, and a defunct refrigerator that held tins of oil-based inks.

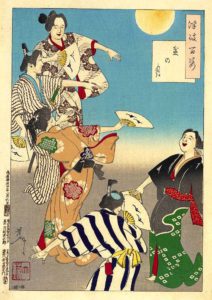

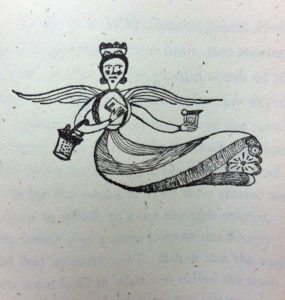

But before any printing, we needed a story. And so I spent weeks in the Shaker Library, researching. I read everything I could find about Deacon James and I looked at everything he had printed. Deacon James first came to the Sabbathday Lake Community as a young man in the late 1700s but it turns out he didn’t become a printer until he was in his 80s. Someone had given the Community some metal type; Deacon James decided the only thing to do was to build himself a press so he could use the type. He built the press in the garden shed, where it remained until the 1950s, when it was tossed out during one of Brother Delmer Wilson’s big clean-ups. In the library, I got to handle all the small books and broadsides that the good deacon had printed… and I got to look at the Shaker Library’s collection of beautiful gift drawings: drawings that were made by Shakers through inspiration they received as gifts from Shakers who had gone before them. They are amazing, each and every one, and Brother Arnold and I decided to use details from these drawings to illustrate our own book about Deacon James.

The board shears / paper cutter was located in the Sisters’ Shop, one of the other beautiful Shaker buildings in the village, the one that also houses the Herb Department, where the Shakers have been packing culinary herbs and herbal teas since 1799. Whenever I had to cut paper for a project, whether for the book or for some other print project, the very air I breathed was spiced with the fragrance of herbs: barrels and barrels of them in the work room, and an attic full of herbs hung to dry. And when I came up with the idea of making our book look like it was found in Deacon James’ old garden shed, Brother Arnold suggested we make a dye from the old butternut trees by the Trustees’ Office. So we gathered up the nuts and boiled them up into a dye in the old Shaker Laundry, in the basement of the Sisters’ Shop, in sight of one of the first washing machines ever made. The Shakers were the first to make washing machines, and they came up with many other conveniences that eventually became part of our everyday modern lives. (This one looks nothing like a contemporary washing machine, though: It’s made of granite and wood. I’m sure it saved plenty of time in its day, but they don’t use it anymore!)

I don’t remember which building we were in when we dyed the book covers and the seed packets we printed for the book, but I do remember we were working on the floor beside a large loom. And we bound the books anywhere we could, sharing the work: Seth and I bound some at the saltbox where we were living; Brother Arnold and the other Shaker sisters and brothers bound the rest when they could in the Dwelling House. And just as suddenly as my summer had begun, it was just about wrapping up: it was early August by then, and my first semester in the MFA in the Book Arts program at the University of Alabama was about to begin. But our book still needed a proper ushering into the world. As it turns out, one of the most important days of the year for the Shaker Community is the Sixth of August, or, as they call it, The Glorious Sixth. It seemed an auspicious day for the book’s unveiling, for it marks the day in 1774 when their founder, Mother Ann Lee, arrived in America from Manchester, England, with a small band of followers to settle here and start life anew. They eventually ended up in Watervliet, New York, and from there the Shaker way spread. At the peak of the Shaker movement in the 1800s, there were more than 6,000 Shakers living in communities throughout New England and Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and even a short-lived community here in Florida. For all of these Shakers, August 6th would be held as a special day in the Shaker year.

It continues so today. These days, the Sabbathday Lake Community is the only active Shaker community left in the world, and there are three Shakers there at Chosen Land: Brother Arnold, Sister Frances, and Sister June. There were more that day in 1996, but since then, some have passed on, and some have left the Community. In fact, many have come and gone over the years, trying the Shaker life. And there are friends. So many of them. Friends who are more like family, and so any gathering at Chosen Land is a big, bustling affair. The preparations for that Glorious Sixth celebration in 1996 were all hustle and hubbub until the supper bell rang, and supper was outside, at wooden picnic tables on the lawn outside the Dwelling House. I probably had trouble buttoning my trousers that night, because the Shakers fed me well all summer long. Brother Arnold and I unveiled our book, presenting a copy of it to each brother and sister. We called it Collected and Compiled by J.H.: The Story, in Many Voices, of Deacon James Holmes, for in researching the book, I realized that the good deacon’s story is best told as a community, which is the basis for Chosen Land and Shakerism in general.

After supper and after our book unveiling, with the setting sun, the magic of the evening truly began. Our small band ventured off to the 1794 Shaker Meeting House, the heart of the village, across the road. We entered as is the Shaker custom, women through one door, men through the other, and we sat on our opposite sides of the room, facing each other, as is also the Shaker custom for each Shaker Meeting. And it is deeply ingrained in my memory what happened next, as the light continued to fade into the darkness of evening, as the dim and flickering lamplight became the only source of light: in the faces of the sisters and other women across from me, I felt I could discern the faces of Shakers throughout time. We may have entered the Meetinghouse in 1996, but it didn’t seem to remain 1996. Sacred spirit filled that sacred space. We sang the song the Shakers always sing for this night: a song called “Mother;” it calls to mind the early history of the Shaker movement. It begins with the words At Manchester in England, this blessed fire began / And like a flame in stubble, from house to house it ran. Certainly tonight Brother Arnold, Sister Frances, and Sister June, the three Shakers that remain in this world, will be singing this old song, and I know they will be joined by an extended gathering of friends. The friends will be from “the world” but still will feel a bit like family, the extended family that radiates out from the Shakers. Chosen Land is a bit like home, after all, and even though Seth and I won’t be present, we will remember all who gather there, especially as the light fades this evening.

Image: One of the illustrations from our book Collected and Compiled by J.H.: The Story, in Many Voices, of Deacon James Holmes, First Printer of the Sabbathday Lake Shakers. It is a detail from one of those Shaker gift drawings I found in the Shaker Library, circa 1830 to 1860, a period of Shaker history known as the Era of Manifestations, a time of very active spiritual revivalism that expressed itself mainly in song and art. The Shakers who drew these gift drawings felt they were acting as medium between the spiritual world and this world, receiving gifts that they then transferred to paper and shared with their Shaker brethren and sisters.