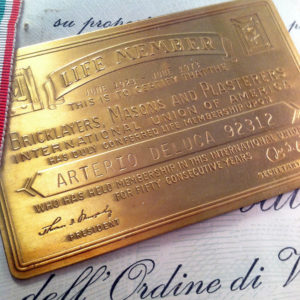

In 1973, my grandfather received his gold union card marking fifty consecutive years with the Bricklayers, Masons and Plasterers International Union of America. He was now a life member. He took that gold union card, and even though his name was misspelled, he put it inside a picture frame along with a certificate and two medals he had earned in World War I serving in the Bersagliere Corps of the Italian army, and he hung the frame on a wall, and that was that. He never talked much about either thing, not the union nor the military service. But he seemed to value both enough to keep these mementos prominently displayed.

We still have that frame: we visited my folks over the weekend and when I asked her about it, my mother pulled the frame from a shelf in a closet. I looked at everything closely, shot the photographs you see here, and returned the frame to its place on the shelf in the closet. But then I paused, picked it up again and set the frame on the bureau, next to the photographs of my grandparents and the statue of St. Rocco. That seemed a more fitting place, especially for Labor Day, a day when we celebrate the American worker. The day has become our country’s unofficial end to summer, but its history is rooted in my grandfather’s time. He was born in the late 1800s, and so was the labor movement in this country. The first Labor Day celebration was organized in 1882 in New York by the Central Labor Union. It was the Fifth of September, a Tuesday, and organizers had no idea how many workers would take part in the parade that wound through Manhattan. There turned out to be more than 10,000; perhaps even 20,000. They carried signs and banners advocating for the rights of workers; things like an 8-hour work day. Twelve years later, in 1894, Congress declared Labor Day a national holiday, falling just as it does today on the First Monday of September.

Grandpa was a union man even longer than he was an American citizen; that particular honor was bestowed upon him in 1935. (My grandmother would have to wait an additional six years for her citizenship.) When times were tough, his work as a bricklayer took him to states far from his home in Brooklyn, as far away as Iowa and North Carolina, wherever there was work; building army barracks, for instance. They worked hard, my grandparents did, and they saved and made real the dreams that first brought them to this country in the early 1920s.

I’m not sure what Labor Day meant to Grandpa, because I never asked him. So much I never thought to ask, but wisdom generally does not come to us until we are older, making us wistful. But Grandpa was a simple man and Labor Day was, I’m sure, just like any other day to him: reading Il Progresso, the Italian paper, with his coffee and toast and cream of wheat, watching Concentration and Eye Guess and Let’s Make a Deal (and shaking his fist at the TV when contestants got too greedy), playing Solitaire and Scopa and Briscola (the last two with the Italian playing cards of swords, cups, coins, and clubs), helping Grandma scour over the lentils, making sure there were no little pebbles mixed in with them. He might have puttered about the garden, bringing in a few late season beefsteak tomatoes. And certainly he passed by the frame on the wall that held the two war medals from Italy and the gold union card engraved with his misspelled name, just as he did the day before, and as he would do the day after, as well.