In Japan it is the time of Obon. It occurs in mid July in some places, and in mid August at others, depending on the region and the use of solar or lunar calendars. But for me, growing up near the Morikami Museum, founded on the site of an old Japanese farming village west of Delray Beach, Obon has always been a late summer holiday, for this is the time it was celebrated at the Morikami; at least until a few years ago, when they decided to rename it Lantern Festival and move it to October.

Obon is the time when the ancestors come back to visit the land of the living for a few days. It has no fixed dates, but where it is celebrated in August, it is generally about this time, these middle days of the month. There are street fairs and there is dancing and music and there are altars in the homes designed to welcome the spirits of those passed. For me, just six months now since I lost my dad, it is a time to think more about him and to welcome his spirit back home to us. Will he be there? I cannot say, but I do feel I’ve had some contact with him over these six months, messages delivered in ways only he and I and a handful of others would understand, bolstering my faith that we can still communicate, still commune, just in ways transformed from what we both had been accustomed to before.

When Obon at the Morikami was in August, I had a way of dragging people there to experience it, even people who hate crowds, and oh, it was a crowded affair. There were one or two times I got Mom and Dad there. I remember them sitting on the grass, watching the fireworks at the end of the festival, and then watching the lanterns set afloat upon the water… hundreds and hundreds of lanterns, carrying the ancestors back to their homes on the distant shore. Such a beautiful sight. My father now part of that luminous procession, sailing upon the water.

Six months ago, I promised you Dad’s stories. So for this Obon, as the Dog Days of summer reach their close, let’s get to a story or two. A good one, I think, for this time of year, is the Watermelon Story. My dad was just a boy, dinner was done, and his mom, my grandma, sent him downstairs––the basement, I imagine, for this was in Brooklyn where they have those things (here we do not)––to get the watermelon after dinner. Down the stairs he went, got the melon, a big oblong one, whole. It was the old fashioned kind that we hardly see any more in these days of seedless melons; probably a Charleston Gray, no doubt half his size. He hoisted it up on one shoulder and headed up the stairs and got all the way to the top and there, at the landing, the delicate balance tilted just a bit, just enough for that melon to tip back slightly. The laws of gravity took over and Dad got to turn and watch the melon crash down the staircase, exploding with each impact on the way down, spraying watermelon pulp and seeds and juice upon the steps and the risers and the walls and the banister and all the wooden balusters to boot. That little kid, my dad Angelo, spent the rest of the night cleaning up the sticky mess. He did, I’m sure, a thorough job.

He still loved watermelon, even after the watermelon incident. Fruit of all kinds, in fact, and I think of Dad most every time I am at a produce market and most every time I am eating fruit. I also think of him when I am involved in some tedious cleaning task. It seems he was charged with lots of these tasks growing up. It was his job to clean the kitchen floor each Saturday night, once everyone had left the room after dinner. He scrubbed the floor, listening to “Gang Busters” on the radio, laying sheets of newspaper on the floor after it was dry. As far as I know, he never delivered papers or sold papers on the corners of Brooklyn, but he did start working for his dad when he was 13, helping Grandpa with his ice, coal, and oil route. One of his first days on the job, my dad put the truck in the wrong gear and drove it right into a customer’s house. The customer made Grandpa promise he wouldn’t harm the kid… but that promise didn’t cover Grandma, who had large arms and who believed in the old proverb, “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” There was probably some sparing of the rod after the watermelon incident, too, before the big cleanup. My poor dad. It was a different time, of course, and Dad took all of these things of his childhood and made them into the stories he told all his life, his honor badges. And told them always with good humor… and like you had never heard them before.

Sometimes I feel like I do that with you, too. But such is the nature of a blog that covers the wheel of the year. The wheel turns and turns, in constant motion, and though we move forward, everything is the same as it was before. It is one of the paradoxes of the seasonal round, making time seem both linear and yet a circular spiral, as well. The players change, but the events remain constant.

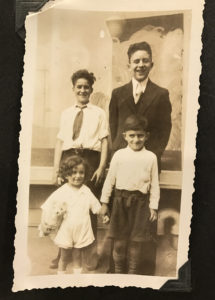

If you wish to learn more about Obon and its traditions in Japan, click here and you’ll be directed to a past Convivio Book of Days chapter about the holiday. As for that photo at the top of the page here, those are the Cutrone Brothers. Aunt Mary, their only sister, is not in the photo; perhaps she was the photographer. The tallest in the photo was the eldest, Uncle Al. Next to him is Uncle Dick. The little one is Uncle Frank, and holding his hand, my dad, looking a bit mischievous. He is in this picture the spitting image of my great nephew Joseph, especially when he is being mischievous. Joseph, my dad’s first great-grandchild. He would make my dad crazy sometimes, like when he locked Dad out of the house and watched with delight from the other side of the glass as Dad yelled and cursed at him. My theory? The little kid that was my dad would rile up Grandma Cutrone just as Joseph would rile up my dad.

We saw this photo for the first time only after Dad’s passing, when my cousin Cammie brought it to us after the funeral. It was one of many photos tipped into old photo albums, the ones with black paper pages and photo corners and captions written in white ink. I had never seen photos of Dad as a child before. It was the most amazing thing.