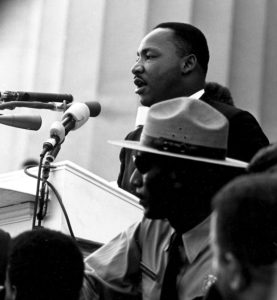

I think it’s fair to say that poet Amanda Gorman stole the show at last week’s inauguration of President Joseph Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. And for sure Bernie Sanders has since then––his mittened image is popping up everywhere right now! But Amanda Gorman: well, she showed us all that day the power of poetry to distill language into emotion as she swept us away with her words.

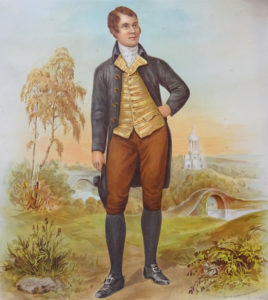

Robert Burns knew a thing or two about that, as well. He was known as the Bard of Scotland in his brief lifetime (1759 – 1796) and still is today. And tonight, throughout Scotland and in the homes of folks who love Rabbie Burns, it is Burns Night, the annual celebration of his birth. It is the traditional night for a Burns Supper. And who knows: someday in this country, perhaps we’ll be celebrating Gorman Night with a Gorman Supper.

The first known Burns Supper took place on the fifth anniversary of the poet’s death, on the 21st of July, 1801. It was celebrated by his friends at Burns Cottage at Alloway. That same year, a group of merchants, some of whom had known the poet, formed the Burns Club, which survives to this day in chapters around the globe. They held their first Burns Supper on what they thought was the poet’s birthday, January 29. That was in 1802. Before the event came around again in 1803, though, they discovered church records in Burns’ home parish that listed the date of his birth as January 25, 1759… and so they moved their annual Burns Supper to the 25th.

And here we are, then, tonight. It is the 25th of January, and in this time of social distancing, our Burns Night Supper will be an imaginary one. Since it is imaginary, let’s make it as perfect as possible. First, a piper will welcome the guests as they arrive. Let’s add a drummer, as well, for full effect. Once the company is assembled and seated at table, the host will stand and recite the Selkirk Grace:

Some hae meat an canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it;

But we hae meat, and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankit.

Robert Burns is not the author of this prayer, but he famously recited it at a dinner given by the Earl of Selkirk. If the language seems both familiar and not, that’s because Burns spoke and wrote in his native Lowland Scots language––a sister language to modern English, but the two diverged independently from the same source (Early Middle English) in the 12th and 13th centuries. Easier to understand, I think, if you speak it aloud as you read (so please do).

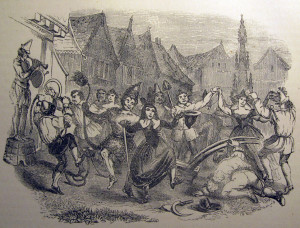

After grace, upon saying Amen, the soup will be served. We suggest cock-a-leekie, a hearty soup of leeks and peppered chicken stock with barley, garnished with sliced prunes. Once the soup is done and the bowls are cleared, we hear the piper strike up the bagpipes again from inside the kitchen. All will rise, the piper will enter and proceed, and behind him, in glorious fanfare, is the chef, carrying in, on a platter, the main course: it is haggis––a savory pudding of mutton or lamb and oatmeal, suet, and spices. This elaborate procession is known as The Piping In of the Haggis. It is the highlight of the evening, accompanied by the Address to the Haggis. It’s a lengthy speech, delivered by our host, or perhaps by an honored guest:

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o’ a grace

As lang’s my airm.

The groaning trencher there ye fill,

Your hurdies like a distant hill,

Your pin wad help to mend a mill

In time o’ need,

While thro’ your pores the dews distil

Like amber bead.

His knife see rustic Labour dicht, [here, a knife is drawn & sharpened]

An’ cut you up wi’ ready slicht, [here, the haggis is cut end to end]

Trenching your gushing entrails bricht,

Like ony ditch;

And then, O what a glorious sicht,

Warm-reekin, rich!

Then, horn for horn, they stretch an’ strive:

Deil tak the hindmaist! on they drive,

Till a’ their weel-swall’d kytes belyve,

Are bent like drums;

Then auld Guidman, maist like to rive,

“Bethankit” hums.

Is there that o’re his French ragout

Or olio that wad staw a sow,

Or fricassee wad mak her spew

Wi’ perfect scunner,

Looks down wi’ sneering, scornfu’ view

On sic a dinner?

Poor devil! see him ower his trash,

As feckless as a wither’d rash,

His spindle shank, a guid whip-lash,

His nieve a nit;

Thro’ bloody flood or field to dash,

O how unfit!

But mark the Rustic, haggis fed,

The trembling earth resounds his tread.

Clap in his wallie nieve a blade,

He’ll mak it whistle;

An’ legs an’ arms, an’ heads will sned,

Like taps o’ thristle.

Ye Pow’rs wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinkin ware

That jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ prayer,

Gie her a haggis!

With the haggis now properly addressed, a whisky toast is drunk, and the company is seated once again for the meal of haggis with neeps and tatties (for us Stateside folks, that’s mashed swedes (rutabaga) and potatoes). There’ll be dessert with coffee––the signal for speeches and poetry to begin––followed by a cheese course. And there will be whisky flowing all the evening long (and since it’s an imaginary supper, no one will get drunk) with a toast to the lassies and a toast to the laddies and a toast to the immortal memory of Rabbie Burns. There will be more poems. And finally, with the work of the supper seemingly over, the host will ask the company to rise and join hands and sing “Auld Lang Syne,” the song for which Robert Burns is most famous. We began our month singing it at New Year’s Eve, and we end our month singing it for Burns Night. (Here’s the version I like best––click here to hear the Revels perform it; it’s a tune you’ve probably not sung the song to, but one that feels, if you ask me, more fitting to the language.)

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot,

and auld lang syne?

- CHORUS:

- For auld lang syne, my jo,

for auld lang syne,

we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

for auld lang syne.

And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere!

and gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak a right gude-willy waught,

for auld lang syne.

The words “auld lang syne” translate essentially to old long since, or old times. The song is one about remembering. And it is right, it is good, to spend some time remembering. Tonight, we remember Robert Burns and we remember those who love him. He was a sentimental poet, Robert Burns, and we need this on occasion: a cup o’ kindness, and the laughter and the tears that come with remembering. Perhaps we cannae have our Burns Supper tonight with friends… but a wee dram of whisky and an old song will do us well in remembering and warming a cold winter’s night. And so we raise our glass to you, and to the immortal memory of Rabbie Burns.

Image: “Robert Burns at Alloway” by John McGready. Lithograph (I think), 1896. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

SHOP OUR VALENTINE SALE!

Our best deal ever awaits you at our online shop: Spend $65 across our catalog and take $10 off, plus get free domestic shipping, when you enter discount code LOVEHANDMADE at checkout. That’s a total savings of $18.50. Click here to start shopping. We’ve got some wonderful new handmade artisan goods from Mexico and some brand new additions from the Sabbathday Lake Shakers, too, to surprise your sweetheart and delight your darlin’. I think you’ll love what we’ve got in store at conviviobookworks.com… and your purchases translate into real support for real families, small companies, and artisans we know by name.