And so we’ve made one full revolution around the sun since my dad passed away. I’ve been a little uncertain just how to approach this week; I knew it would not be an easy one. I know everything I did last year on February 7th, 8th, and 9th. These things are imprinted on my memory. Seth and I were with friends at a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Kravis Center in West Palm Beach on the night of the 7th. Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich were on the program. I was there but I was equally not, as I sat there in the box, worried about my dad, acknowledging for the first time, as I listened to the Rachmaninoff piano concerto, that maybe he was not going to get better. On the 8th, Seth and I went to see Dad in the morning at the rehabilitation center he’d been at since late January. He was in good spirits. We left, for we had to go to work, and we had breakfast at a nearby bagel place, a place with a chain to keep the people in line in check, a place that drained the energy from me. But we ate there all the same. And then we parted, Seth and I, he to his job and me to mine. All day long I worked but I wanted to leave to go see Dad. Late in the afternoon, I did. When I arrived at his room, he was surrounded by nurses. They were moving him to Medical ICU. “To keep better watch on him,” they said. I watched from a corner of the room as they made things ready for the move. Dad seemed ok. I walked alongside his bed as they rolled him down the corridors, down the elevator, into the ICU, where I was told to wait outside. I called my mom and sister, and I called Seth. They came and waited with me in the waiting area. We finally got inside, late in the evening, to visit with Dad. He seemed ok then, too. We talked some, but he was tired. And then the ICU nurse came and told us it was time to go. We didn’t want to, but we had to, I guess. We said goodnight to Dad. We each kissed him. We each said, “I love you.” He told us he loved us, too. We went to eat, at Brewzzis, probably their last customers of the night. We had the same waiter that served us a few nights earlier, when my cousin Al came to visit Dad, the night that Dad was so animated and so much like his usual self, it was hard to remember he had had a stroke. The waiter remembered us. When we were done, we said goodnight in the parking lot; my sister and my mom went home, Seth and I went home. We fed the cat. We showered. We went to bed. We kissed each other goodnight. I fell asleep. Sometime past midnight, the phone rang. I jumped out of bed. I answered. It was my sister; Dad had gone into cardiac arrest. We rushed to the hospital. We met my mom and sister there, all of us anxious, nervous. It was after hours, so they wouldn’t let us in. We explained. We waited, and waited, and waited. Finally, a security guard came and took us to ICU. We opened the door. The nurse calmly told us she was so sorry. And that was that.

My dad had been diagnosed with cancer years before. It was prostate cancer that had spread to the bones. But never did he “seem” to have cancer. He never had chemo, he never lost weight, he never lost his hair, all the things that I had thought, in my limited knowledge, came with the disease. He carried on, just as he always did. He had spinal stenosis, too, and it got more difficult for him to walk as the years passed. A cane would have been a great help, but he was too proud to use one. Dad never liked to call attention to himself. He began radiation treatments at the start of January last year, to help control the cancer that was beginning to spread more rapidly. His doctor said that he was responding really well to the treatments. There’s a bell there at the center that folks who complete their treatments ring––a right of passage of sorts. I was excited for Dad to ring the bell after his last treatment. He laughed at me. “I’m not ringing that bell,” he said. To him, ringing a big brass bell was no better than being seen with a cane.

He never did ring it. He had a stroke the morning he was supposed to have his last radiation treatment, which is what brought him to the hospital in Boca Raton and a week later to the rehabilitation center in Delray Beach. He even took his stroke in stride. There was going to be a long road of therapy ahead to learn how to walk again, but his speech was fine. He was a master at making us think all was well. In the end, I think he checked out on his own terms. He did so gently and in his own perfect timing. We said goodnight, we said our I love yous, and he went to sleep. Who can ask for better than that?

I wish I wasn’t so nice about quietly waiting all those hours in the waiting area while he was alone in ICU. I did what I was told, and think they just forgot about me, and it bothers me sometimes that I just sat there. I wish I had known to call my nephews. But things didn’t seem that bad. I wish we had been there with him at the very end, all of us. But we weren’t.

Dad gave us so many gifts over his lifetime, and the last one he gave us was a peaceful transition. Actually, it wasn’t the last gift he gave us. There have been so many little things that have happened over the course of this past year, coincidences maybe, but some have been just too coincidental. I never know when these gifts will come, but they do. It is my job, I think, to be open to them, to believe that there are occasional passings across that bridge that keep us connected. And so I meander through this week of memories, bumping through each day of it, not sure what to do or what not to do. Maybe some of you are going through weeks like this of your own. I’m right there with you; I understand. There is no right or wrong way to do any of this. We just do it. And we hope we do it well, pushing through to a week that holds different memories, as the planet we stand upon keeps spinning and traveling around the star that holds us and gathers us in.

* * * *

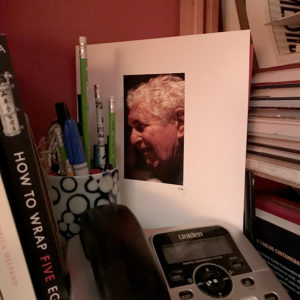

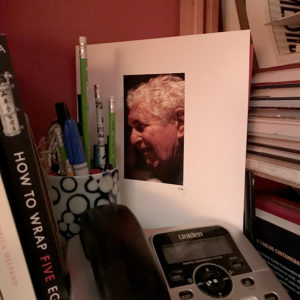

Opening image: Seth and I keep this photograph of my dad in the bookcase in our living room. Paula Marie Gourley was the photographer, three or four years ago, snapping the picture of Dad in his home, which always was his favorite place to be.

Dad loved home, but he also loved cars. Dad was an auto mechanic most of his life––a Doctor of Engines, he would say, or a Doctor of Automobiles. In 1974, he bought a burgundy Cadillac Coupe De Ville. Not long after the new car purchase, the three of us were in the car, Mom, Dad, and me. Mom just happened to reach across the dashboard for something, and as her hand passed in front of the radio, the station changed. We all agreed that that was pretty odd, but sure enough, when she reached over a second time, again the radio station changed. It happened again and again and we decided it was Mom’s diamond ring that was causing this. I happened to have a ring in those days, too, with a little ruby and a little diamond. I waved my ring in front of the radio and the station changed for me, too. For months, Mom and I believed our rings had the power to move the radio dial in that 1974 Cadillac.

Turns out there was a button on the driver’s side floor that controlled the radio. Each time one of us passed our ring in front of the radio, Dad would secretly step on the button to activate the station change. We were convinced it was some sort of magic, the diamonds operating on a higher frequency. That was my dad, though: he dealt in magic of a practical sort, and helped you believe you could do anything you wanted to do.