Apologies are in order: I’ve not had much time to sit and write this month, and already it’s not long until the Walpurgis Night celebration we discussed in the previous post. That holiday comes next week, as April shifts to May. But it’s St. Mark’s Eve as I sit and write this, and with the rising sun on April 25, it will be St. Mark’s Day. It is the day in northern climes when most migratory birds are thought to arrive and it is a day to utter blessings upon the newly-sewn springtime crops. (I must apologize, too, for putting the incorrect date for the occasion on the Convivio Book of Days calendar for April, where St. Mark’s Eve is listed as April 25, and St. Mark’s Day as April 26. In fact, the Eve is on the 24th and St. Mark’s Day is on the 25th.)

In Venice, a city watched over lovingly by St. Mark from the Basilica di San Marco, thousands of rosebuds will be exchanged, a custom emerging from a tragic old love story: Many centuries ago––the eighth century, to be precise––there lived in Venezia a humble troubadour called Tancredi, who fell madly in love with the doge’s daughter, Maria. Maria was equally enamored of the troubadour, but her father was not at all pleased with this. A man of so low a social standing (a troubadour, pfft!) wooing the doge’s daughter? It would never do for the doge.

A wiser man would have despaired, but Tancredi, he mustered up all his passions and instead, went off to prove his worthiness, off to war in a distant land, in hopes of returning triumphantly, thereby impressing his potential future father-in-law. Tancredi proved heroic and victorious through each battle, but alas, his return was not meant to be, for just before he was to come home to his beloved Maria and his beloved city, the troubadour was mortally wounded in one last fatal conflict. His good friend Orlando rushed to his side as Tancredi fell, dying, upon a rose bush. And in his final moments on this earth, far from his intended, Tancredi plucked a single rosebud and gave it to his friend, begging of him one last favor: to bring the flower to Maria. Orlando did just that. She received the blood-stained bloom, and the news of her love’s fate, on St. Mark’s Day, the 25th of April, and that night, she died upon her own bed, holding Tancredi’s rosebud, a symbol of love eternal. And to this day, in memory of the troubadour and the doge’s daughter, rosebuds are exchanged in Venice on the Festa di San Marco.

For dinner on St. Mark’s Day, most Venetians will eat a simple dish: risi e bisi in the Venetian dialect: a risotto of rice and peas with pancetta and onion, in years past brought with great ceremony to the doge. Peas as a symbol of spring, rice for abundance. The day marks, as well, Liberation Day throughout Italy: the Festa della Liberazione. It is a national holiday, marking the day in 1945 that ended the Fascist regime and the Nazi occupation of Italy.

St. Mark is, of course, one of the evangelists, and he is credited with writing the Second of the four Gospels. He is often depicted writing or holding his Gospel, but he is also symbolized by a winged lion, which is thought to come from his description of St. John the Baptist as “a voice crying in the wilderness.” The wings come from Ezekiel’s vision of four winged creatures as evangelists. He lived for many years in Alexandria and was martyred there, too, but his relics were stolen from Alexandria and brought to Venice in 828, where they are enshrined at the basilica on St. Mark’s Square… where so many rosebuds will be exchanged today, symbols of love eternal.

SHOP OUR SPRING SALE!

It’s still spring and at our online catalog right now, you may use discount code BLOSSOM to save $10 on your $85 purchase, plus get free domestic shipping, too. That’s a total savings of $19.50. Spend less than $85 and our flat rate shipping fee of $9.50 applies. CLICK HERE to shop; you know we appreciate your support immensely.

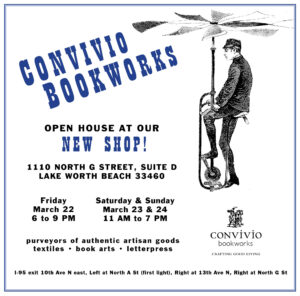

COME SEE OUR NEW SHOP!

We make small improvements to our new shop every week. Currently, we are building a staircase to the loft, and we’re planning a proper Grand Opening for Old Midsummer in late June (in fact, please go ahead and put the weekend of June 21, 22, & 23 on your calendar). I’ll keep you posted about it here and on our Instagram and Facebook pages (@conviviobookworks). We don’t have regular hours currently, but until we do, if you’d like to come shop or just see the place (or us), we welcome you to come visit by appointment. Email us to schedule a time. The new shop is located at 1110 North G Street, Suite D, in Lake Worth Beach, Florida 33460.

Image: The flag of La Serenissima: the Republic of Venice, with the image of San Marco as a winged lion, holding his Gospel.