FIFTH DAY of CHRISTMAS:

Bring in the Boar

Today is the perfect day to sing “The Boar’s Head Carol!”

The Boar’s head in hand bear I

Bedecked with bays and rosemary

And I pray you, my masters, be merry

Quot estis in convivio! [So many as are at the feast!]

The Boar’s head, as I understand,

Is the rarest dish in all the land

When thus bedecked with a gay garland

Let us servire cantico! [Serve with a song!]

Caput apri defero,

Reddens laudes Domino! [The Boar’s head I bring, giving praises to God!]

Our steward hath provided this

In honor of the King of bliss,

Which on this day to be served is.

In Reginensi atrio! [In the Queen’s Hall!]

Caput apri defero,

Reddens laudes Domino!

And so on the Fifth Day of Christmas, tradition calls for bringing in the boar. This is a tradition that goes back many many centuries in Britain and is associated especially with Queen’s College, Oxford. It’s a tradition that persists despite wild boar being virtually extinct from Britain since at least the 12th century. To the Celts, the boar was sacred, a gift from the Otherworld, ferocious, feared, respected, and the provider of the great feasts of midwinter.

Of course there’s an awful lot of feasting this time of year, what with Christmas and New Years and Twelfth Night. But there is a reason for this, as well. These Twelve Days of Christmas stand outside of ordinary time. In earlier days, most folks did not work for the duration of Christmastide, so big feasts were easier to conjure. In agricultural communities, midwinter was also the time to thin out the herds, so meat was plentiful. Whether they were bringing in the boar or some other beast, the Fifth Day of Christmas had long been a day of great feasting.

Nowadays, we tend to be back to work soon after Christmas Day, so a feast for the Fifth Day of Christmas is not as practical as it once was. But we do have to eat. Why not deliver the meal tonight to the table with pomp and ceremony? Acknowledge that sustenance comes not without sacrifice, be it the death of animal or plant. Bring even the simplest meal to the table tonight in this spirit of humility and appreciation and festivity and I’d say you’ve got the spirit of the day down pat.

“The Boar’s Head Carol” is particularly dear to us here at Convivio Bookworks, for the song is the source of our name. The song goes back to at least the 15th century. It is a macaronic carol, meaning it combines two languages (English and Latin) and the version we sing most often today is one that was first published by one of the first printers in London: Wynkyn de Worde. He published it in a book he printed in 1521, titled Christmasse Carolles. I did a paper on Wynkyn de Worde in grad school in Marcella Genz’s History of the Book class, only because I liked his name so much. I didn’t know about his book at the time, but now I’m rather pleased that Wynkyn de Worde and I have such a fine connection, and I’m sure, considering he printed a book of Christmas carols in 1521, that he was one to shout as much as Seth and I do, “Welcome Yule!”

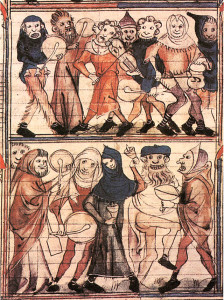

Image: Bringing in the Boar’s Head by St. J. Gilbert, Christmas Supplement to the Illustrated London News, 1855. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

![Bring in the Boar's Head [Illustrated London News]](http://www.conviviobookworks.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Bringing_in_the_Boars_Head-220x300.jpg)