It’s the 22nd of February, and in Ancient Rome, this day would bring each year the Feast of Concordia: a feast of goodwill and harmony. It is perhaps a sign of our times (or of our natures) that the word concord does not get used very much these days, and even accord is a word we hear rarely; yet we are all too familiar with the word discord. Concord is agreement, harmony, unanimity… and discord? Well, we all know about that.

The concept behind Concordia is simple: gather family and friends for a meal and at that meal, settle all disputes. It is a day to make amends for wrongs done, a day to reconcile differences. To put discord to rest and to nurture concord. To do this over bread and wine is a simple, humble act.

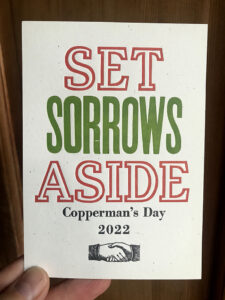

If there is discord in your life, perhaps this is the ritual needed to turn that into concord, to activate peace and harmony. To be sure, the concord involves a willingness from both parties, and someone, of course, must have the courage to take the first step. But being willing to let go of bitterness and to activate concord is a dramatic change, and even if you find the other party unwilling, you have given yourself a great gift in releasing the power the discord has over you. That is the gift of this day, the gift of Concordia. And so we wish you harmony and goodwill. And perhaps it is auspicious that our annual Copperman’s Day print is finally ready, for the message, I think, has some relation to all this: there is no joy in discord, but there is plenty of sorrow to be found there. This year’s Copperman’s Day message is simple: Set sorrows aside. The text is from a song recorded by the Boston Camerata for their collection, An American Christmas, which was in heavy rotation here at Convivio Bookworks while this letterpress project was in the works. The song, called “A Virgin Unspotted,” is found in Wyeth’s Repository of Sacred Music, Part Second (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, 1820). There are two repeating, alternating choruses:

Then let us be merry, cast sorrow away:

Our Saviour Christ Jesus was born on this day.

Aye and therefore be merry, set sorrows aside:

Christ Jesus our Saviour was born on this ‘tide.

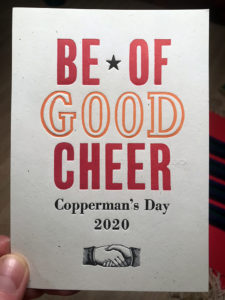

Though rooted in a religious text and song, our Copperman’s Day print message is truly universal and non-denominational. As for Copperman’s Day: it is an old Dutch printer’s holiday, falling on the First Monday after Epiphany each January. It was traditional on this day for printers’ apprentices in Holland to receive the day off to work on their own projects––usually small printed keepsakes that they’d sell for a copper. And though we began our print on Copperman’s Day, I didn’t finish the printing until a week or so ago, and the cutting was just done on Friday. We are belated for almost everything these days.

If you sent us a Christmas card, this print will soon be on its way to you in exchange. And if you’d like to purchase some of these or any of our other Copperman’s Day prints that we’ve made through the years, click here to shop. This is the seventh in almost as many years (I couldn’t quite muster the energy to create one in 2018 and 2019). These miniprints happen to be standard postcard size. Each is printed by hand from historic wood and metal types in multiple, separate print runs on the Vandercook 4 printing press in our Lake Worth studio on recycled French Speckletone papers.

SPECIAL DEAL! Order 3 or more of our mini prints (Copperman’s Day prints, B Mine Valentines, and our famous Keep Lake Worth Quirky prints) and use the code COPPERMAN when you check out; we’ll take $5 off your domestic order to help balance out our flat rate shipping charge of $9.50. Of course, you can spend $60 or more in our shop and earn free shipping, too! Click here to shop Copperman’s Day… and here’s to concord and to casting sorrow away!