I am not the best example one could hold up of a good Catholic. I pray, but I’ve not been to church in years, and I’ve not confessed to a priest for several years more, and more often than not in recent memory if you’ll find me at a church service at all it’s at the Episcopal Church (which feels to me, as a solid traditionalist, more Catholic than the Catholic Church these days, for the Episcopalians use the same language we Catholics used to use in Holy Mass––plus, to be honest, they seem a lot less judgmental). Covid has kept Seth and me away from places of worship these past two years, but on Thursday night, for Holy Thursday (or Maundy Thursday), I plan on donning my face mask and venturing forth and finding my place again (and Seth already knows he’ll be joining me).

It is not so much the Mass that I love and miss; it’s the quiet, open spaces between the official ceremonies. Just like good writing or good music is all about the open spaces between sounds or words, to me, Holy Week is the same. Last Sunday was Palm Sunday and I’m not so interested in that; I’ve never quite understood it. But I am interested in what happens now, as the week progresses toward its close, for on Thursday night, here ends the Lenten season, and here begins the Easter or Paschal Triduum: Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday: the Last Supper, the Passion, and the Resurrection through Saturday night’s Easter Vigil. Most especially, it is Holy Thursday I love.

Passover, too, will begin with the setting sun on Friday. Passover and Holy Week are, I think, constant companions, but what I know about Passover is not much and mostly is in relation to my Catholic upbringing and to Passover’s connexion to the Easter story. I know that Passover commemorates the liberation of the Israelites from their slavery in Egypt, and I know what a friend told me once, which has always resonated with me about the holiday: “We are traveling through the desert with our ancestors via a table filled with metaphor and symbolism.” The meal is the seder, the same meal that Jesus celebrated with his disciples in the upper room on that Holy Thursday night before he died. Pesach is the Hebrew name for Passover, and, as words go, Pesach informs the name for Easter in many languages: in Italian, for instance, Easter is called Pasqua. In French, it is Pâques, in Portuguese, Páscoa, and in Spanish, Pascua. (The English word “Easter” does not share this etymological relation to Pesach. Our word for the holiday comes down from the Old English Eostre, related to the German Ostern and an Anglo-Saxon goddess whose feast day was celebrated around the Spring Equinox. Fascinating, too, but a whole different story.)

Holy Thursday, though: It is, to me, one of the most beautiful nights of the year––a quiet and unassuming holiday/holyday, remarkable in its consistency, for the moon is always big and beautiful this night, hauntingly present, a constant companion as we make our pilgrimage in an old tradition that would have us visit three churches over the course of the evening. My grandmother, Assunta, taught me that custom, but, for some reason, not until the Holy Week after Grandpa had died. I think suddenly these old traditions meant more to her. I discovered then that the world is different at night. Churches glowing from within, moonlight reflecting on columns and limestone figures. Astonishingly quiet, serene stillness.

The actual Holy Thursday mass in most churches comes around sunset. It is the Mass of the Lord’s Supper, commemorating that Passover seder, the last supper so often depicted by artists. Jesus began by washing the feet of his disciples, a humble act accompanied by the suggestion that we, too, should not be above doing even the lowest things for others. At supper, he broke bread and passed the cup of wine: the central act of every Mass.

The Holy Thursday Mass Seth and I used to attend is a trilingual one, in English, Spanish, and Creole. It’s long and it’s crowded (and definitely not Covid-safe). It is the one Mass each year in the congregation where folks from so many diverse communities finally come together. For years I would seek out and sit next to an old Creole woman who reminded me of my grandmother, but I’ve not seen her for many years now, even before Covid, and I suspect by now she is long gone, into the ages. Each year I would sit there with people I did not know at all. I would sit there and think of my grandmother and the old Creole woman who had no idea she was so important to me.

The First Reading is in one language, the Second Reading in another, and the Gospel in the last of them. If you don’t know the language being spoken, you read along on your own. And as crowded as it is, still there are two choirs: one singing in English, the other in Creole, coming together, too, for this one night each year. The Creole songs are long and mysterious. One of them is sung to the tune of “My Old Kentucky Home.” They sing in Creole while I remember what I can from Stephen Foster’s song and each year they sing that song, I think of the small scrap of paper found in Stephen Foster’s pocket after he died. On it, he had scribbled five touching words: Dear friends and gentle hearts. That’s exactly how I feel each year on this night.

The Mass ends with the transfer of the Blessed Sacrament to the chapel while the congregation sings the Pange Lingua, acapella. Its more proper name is Pange Lingua Gloriosi Corporis Mysterium, an old hymn written in Latin by St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. “Mysterium” is very appropriate, for this is a night wrapped in mystery and beauty, both of which truly begin once the Pange Lingua is done. There is no real end to the Mass. A small bit of chaos ensues as church workers begin to prepare for the Good Friday services the next day. People get up and leave, others mill about, and it’s noisy hustle and hubbub for a good 20 minutes until, eventually, the noise fades away as the church empties to just a few hardy souls who are there to sit. Some are in prayer, some are in reflection. Most, perhaps, are like me: doing some of all those things but also just being part of something bigger than ourselves, as it should be, in the company of others.

The tradition varies, apparently. The one that Grandma passed down to us is to visit three churches on this night. But I’ve heard of some people visiting seven churches. Both are magical numbers: 3 for the Trinity, of course, and for the three aspects of the Goddess (virgin, mother, crone), amongst other things, and 7 for more things than you might imagine: the seven sacraments, the seven days of creation, the seven sorrows of Mary, seven loaves and fishes… Still, three churches is plenty. Grandma may have been pious but she was not a martyr.

So this year, three years into Covid, we will skip the Mass but Seth and I will return again to our pilgrimage. It will take us first to St. Anne’s, the small old church surrounded by the tall buildings of Downtown West Palm Beach, and then across the lagoon to the much grander St. Edward’s in Palm Beach, which rivals the Vatican, and finally down the road to Bethesda by the Sea, where each year we wander the grounds, looking at the gargoyles and the crypts and the fountain, and we look for the boar in the stained glass window that shines onto the courtyard. We will sit, we will kneel, we will wander and wonder in the still and dark candlelit night, and me, I will have in mind all those who have gone before us doing this very same thing. This is the value of ceremony and tradition to me: this connexion across time and space. And no matter where we go this night, the moon is there, too: tagging along, trusted companion, never tiring, illuminating the night and the trees as much as the churches themselves illuminate their stained glass windows shining out from within. No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lamp stand, and it gives light to all in the house.

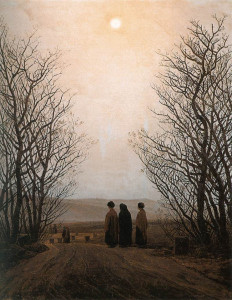

So, I’m not the best example of a good Catholic and perhaps not the best example of a good writer, for this is a re-worked version of an essay I’ve written many times before, and one would think I would just call it good at some point, but instead, I keep rehashing it and maybe someday I’ll have it down pat. I beg your patience. Our image for today is also one I’ve used before: it is “Christ on the Mount of Olives” by Paul Gauguin. Oil on canvas, 1889 [Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons]. It is one of my favorite paintings that resides at the Norton Museum here in West Palm Beach, which still to this day I refer to as the Norton Gallery, which was its name before the gallery graduated to museum status. It is the same place I’ve written about in the past––usually for All Hallow’s Eve––when I tell you about the Lake Worth pioneers who are long gone, and whose graves are beneath a trap door under the stage of the auditorium of the Norton (if the stage even exists anymore). I suppose when you get right down to it, I am a person who does his best to keep the channels open: channels across time and space, spaces between trap doors and sunlight. I don’t want people forgotten once they leave this world. It’s a mighty responsibility to keep them all in mind, but this is what I do. And this is a big part of what I love about this holiest of weeks.