I am writing this in a church, which probably is not very reverent of me. It is the overnight watch, as Holy Thursday dissolves into Good Friday. The Easter Triduum. Apologies for my irreverence, and also for years of leading you astray, as I’ve told you for years now that lent, that somber season that leads to Easter, ends with the Easter Vigil Mass on Holy Saturday. Well, that’s not true. It ends, I’ve learnt just tonight, with the Triduum of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. And so I apologize for years of misinformation.

While I’m pretty good with the secular stuff, I am certainly not your best source for liturgical information. Although I love churches (especially old ones), I have not been a very good churchgoer for a while now. My last time in a church was for Dad’s funeral mass last February, before lent even began, and not since last Easter before that. But I love ceremony and I love tradition, and I love this night. It was my grandma Assunta who taught us the tradition of visiting three churches on Holy Thursday, though three may have been a tradition of her own––visiting seven is more traditional, an Italian tradition coming out of the seven basilicas of Rome and the seven stations of the cross. But we do what we know and three is what I have always known. And there are meditations that we are supposed to reflect upon while we are in those churches. But me, I am a visitor. I like to visit and sit in the company of those I love, and so this is what I do here, too. It may be just me and a few other souls in this dark church tonight, but in my heart all the ones I love are with me, too. My whole family. No one is missing. This is especially important to me this year.

Hide Not Your Light

Tonight is one of the most beautiful nights of the year: Holy Thursday. A quiet and unassuming holiday/holyday, remarkable in its consistency, for the moon is always big and beautiful this night, hauntingly present, a constant companion as we make our pilgrimage in an old tradition that would have us visit three churches over the course of the evening. The world is different at night. Churches glowing from within, moonlight reflecting on columns and limestone figures. Astonishingly quiet, serene stillness.

The actual Holy Thursday mass in most churches comes around sunset. It is the Mass of the Lord’s Supper, commemorating that last supper so often depicted by artists. Jesus began by washing the feet of his disciples, a humble act accompanied by the suggestion that we, too, should not be above doing even the lowest things for others. At supper, he broke bread and passed the cup of wine: the central act of every mass.

The Holy Thursday mass I’ll attend tonight will be trilingual: English, Spanish, and Creole. It’s long and it’s crowded but I love it. It is the one mass each year where folks from so many diverse communities come together. For years I would seek out and sit next to an old Creole woman who reminded me of my grandmother, but I haven’t seen her these past two years, and so I sit there with people I do not necessarily know and I think of my grandmother and the old Creole woman who had no idea she was so important to me.

And so the First Reading will be in one language, the Second Reading in another, and the Gospel in the last of them. If you don’t know the language being spoken, you can read along on your own. And as crowded as it is, still there are two choirs: one singing in English, the other in Creole, coming together, too, for this one night each year. The Creole songs are long and mysterious. One of them is sung to the tune of “My Old Kentucky Home.” They sing in Creole while I remember what I can from Stephen Foster’s song and each year they sing that song, I think of the small scrap of paper found in Stephen Foster’s pocket after he died. On it, he had scribbled five touching words: Dear friends and gentle hearts. That’s exactly how I feel each year at this mass.

The mass ends with the transfer of the Blessed Sacrament to the chapel while the congregation sings the Pange Lingua, acapella. Its more proper name is Pange Lingua Gloriosi Corporis Mysterium, an old hymn written in Latin by St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. “Mysterium” is very appropriate, for this is a night wrapped in mystery and beauty, both of which truly begin once the Pange Lingua is done. There is no real end to the mass. A small bit of chaos ensues as church workers begin to prepare for Good Friday, which is tomorrow. People get up and leave, others mill about, and it’s noisy hustle and hubbub for a good 20 minutes until, eventually, the noise fades away as the church empties to just a few hardy souls who are there to sit. Some are in prayer, some are in reflection. Most, perhaps, are like me: doing some of all those things but also just being part of something bigger than ourselves, as it should be, in the company of others.

The tradition varies, apparently. The one that my grandmother Assunta passed down to us is to visit three churches on this night. But I’ve heard of some people visiting seven churches. Both are magical numbers: 3 for the Trinity, of course, and for the three aspects of the Goddess (virgin, mother, crone), amongst other things, and 7 for more things than you might imagine: the seven sacraments, the seven days of creation, the seven sorrows of Mary, seven loaves and fishes… Still, three churches is plenty. Grandma may have been pious but she was not a martyr.

My pilgrimage each year takes me from my small old church surrounded by the tall buildings of Downtown West Palm Beach, across the lagoon to a grand church in Palm Beach that looks like it’s come out of the Vatican, to a humble church in Lake Worth. I make these rounds each year on this night, sitting, kneeling, remembering those who have gone before us doing this very same thing. This is the value of ceremony and tradition to me: this connection across time and space. And no matter where I go this night, the moon is there tagging along, trusted companion, never tiring, illuminating the night and the trees as much as the churches themselves illuminate their stained glass windows shining out from within. No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lamp stand, and it gives light to all in the house.

This is a reprint of a chapter written for Holy Thursday, 2014. The sentiment is the same and the moon, full last night, will be joining us as we make that annual pilgrimage. Perhaps the old Creole woman will be back this year. Then, tomorrow, we will do our Easter baking with the rest of the family, preparing the things we love for Sunday’s big dinner. Today’s image was taken one Maundy Thursday at the courtyard at St. Edward’s Church, Palm Beach. The world is different at night, with its distinct mysteries and a haunting beauty not open to us in daylight. Thanks for coming along with me on the journey.–– John

Balance

By the time you read this, spring will have made its arrival by the almanac: the equinox––vernal here in the Northern Hemisphere, autumnal in the Southern––came and went at 12:30 in the morning (Eastern Daylight Time) this 20th day of March. In traditional reckoning of time we are at spring’s height, its midpoint, and now are on the downhill ride toward summer. But no matter how you reckon your time, what is clear in all cases is this: balance. Day and night now are just about equal in length no matter where we are on the planet, and there is something about that balance that is wonderful (as in full of wonder): no matter what concerns we have in our lives, be they major or minor, the celestial clockwork continues. If a vast planet of oceans and mountains can achieve balance, it gives us hope that we can, too.

It is, as well today, Palm Sunday, setting the events of Holy Week in motion. We enter into the highest days of the Christian calendar. I have said this before in the Convivio Book of Days: Palm Sunday has never been a favorite day of mine. The Mass is really long, the congregation gets to read but it’s almost always lackluster and halfhearted, and I never know if I should feel mourning or celebration. Father Seamus likes to say that attendance goes up whenever they give something away at church, even if it is just a couple of palms, even in this chlorophyll-laden land where we see palm trees every time we open our eyes.

One of the more charming traditions for the day is the fashioning of crosses out of those palms. Some can be very elaborate: my mom’s cousin’s husband could turn a single palm frond into a cross with two flowers bursting out of its center. A lesser known tradition would have us eat figs on Palm Sunday, which comes out of the story of Christ’s cursing of the fig tree, which occurred soon after he arrived in Jerusalem:

In the morning, as he was returning to the city, he became hungry. And seeing a fig tree by the wayside, he went to it and found nothing on it but only leaves. And he said to it, “May no fruit ever come from you again!” And the fig tree withered at once. (Matthew 21: 18-19)

And even this irritates me about Palm Sunday. This story sounds like something Teenager Jesus might have done. Why curse a fig tree for having no fruit? Be that as it may, some people make sure to eat figs on Palm Sunday just because of this verse and a similar one in Mark. They’ll be eating dried figs, for sure, because it’s not fig season. You’d think Jesus would have known that, too.

And with Palm Sunday’s close, we begin to clean. Just as we “made our house fair as we are able” during Advent, these next few days are days of making our house fair as we are able for the coming feast of Easter. By Wednesday night, the moon will be full and all should be done, and all distractions set aside, for the mysteries of Easter begin with Holy Thursday: one of my favorite nights of the year, a night rich with ceremony and ending in pilgrimage and peaceful contemplation, and I am of the mind that my disdain for Palm Sunday is more than made up for by my love for Maundy Thursday. And there it is, perhaps: that balance, manifested, as we stand here on a planet midway now between longest night and longest day.

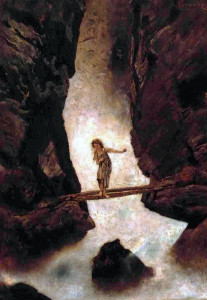

Image: “The Waterfall” by Anton Romako. Painting, late 19th century. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.