In Sweden, the twentieth day after Christmas is a significant one: January 13 brings St. Knut’s Day, and for Swedes, this is the day to toss out the Christmas tree. First, it must be plundered: if there are cookies and foil wrapped chocolate ornaments still on the tree, this is the day they get gobbled up! Gingerbread houses get smashed and eaten! Every last candy cane is consumed! It is a proper and festive end to the Yuletide season.

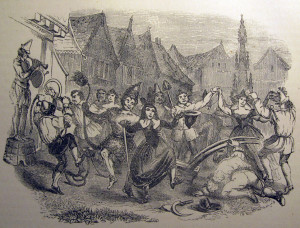

The Swedes, who like to sing and dance around their trees when Christmas Eve comes (have you seen the 1982 Ingmar Bergman film Fanny and Alexander?) will be singing and dancing around their trees again today before the tree is plundered and tossed. The tossing, traditionally, was out the window, though these days that practice is frowned upon; it’s more common nowadays for clubs and civic organizations to collect the discarded trees. They stow them away for Walpurgis Night bonfires at the end of April. All of these things––the dancing, the singing, the bonfires––suggest to me that Sweden is a pretty decent place to live. Plus, how nice to have a proper and widely acknowledged Close to Christmas day? Here in the States, where it’s not unusual to see a tree tossed sadly on the curbside as early as the 26th of December, I’d say we could use a bit of guidance like this (not to mention a bit of celebration, too, to close the season).

This year, the 13th of January also brings Plough Monday and Copperman’s Day. Both of these obscure holidays fall each year on the Monday after Epiphany, and here we are today at that Monday. Copperman’s Day is the more obscure of the two: It is an old Dutch printer’s holiday, and on this day, the print apprentices would get the day off to do what they wished in the print shop. The resulting prints they made, of their own design and creation, they’d sell for a copper. Plough Monday relates to St. Distaff’s Day, which was last week, on the day after Epiphany. St. Distaff brings the traditional Back to Work day for the women (back to their spinning), while Plough Monday brings the traditional Back to Work Day for the men (back to the plough).

As for us in this house, we’ll be ignoring these things, for the most part. Our tree, which is still lovely and thirsty and thriving and beautiful, will remain standing in the living room, where we intend to keep it, along with all the other Christmas greenery, until Candlemas Eve on the First of February. This is a tradition just as old, I imagine, or perhaps even older than the St. Knut’s tradition in Sweden. And we’ve been back to work since last week (employers these days don’t want us taking off all the days ’til Plough Monday). And whilst I do make a Copperman’s Day print each year, it’s a rare event indeed when it actually is done on Copperman’s Day. If I get to organize my print shop tonight and set some type, that alone will be a miraculous thing. Expect the newest Convivio Bookworks Copperman’s Day print by early February (if all goes well).

However, I can tell you what we do plan on for tonight: an illuminated Christmas tree, and delightful Swedish Christmas music in the house on this long winter’s night. The songs (like “Nu är det Jul Igen,” a 500-year old Dancing Around the Tree song whose lyrics essentially translate to Now it is Christmas again and it will be Christmas until Easter –– no, that isn’t true, for in between comes Lent) are full of wonder and joy, which is perhaps not what one would expect from a land so dark and cold at this time of year. Or perhaps it is just what you’d expect. I can’t say. All I know is we intend to make it a fun night here in our home, and I encourage you to do the same.

Today’s chapter of the Convivio Book of Days comes to us thanks to the suggestion of Convivio friend Rachel Kopel in San Diego. We spend most Friday afternoons together on Real Mail Fridays, the letter writing social I host on Zoom most Fridays for the Jaffe Center for Book Arts. Rachel joins us, leaves sometimes for ukulele practice, then joins us again before the social is done. We’d love to have you join us, too. We meet the most interesting people at Real Mail Fridays!

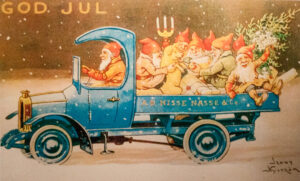

Image: A Swedish penny postcard for Christmas, printed in the early 1900s. The artist is Jenny Nyström. The characters in the truck are called Tomten: Swedish elves who live in barns. God Jul (Happy Christmas).