NINTH DAY of CHRISTMAS:

St. Genevieve’s Day

We are in the midst now of a more contemplative period within the Twelve Days of Christmas. Yesterday we remembered St. Macarius, or St. Macaroon the Confectioner, and tomorrow we remember a few other saints (four of them, to be exact). Today, though, this Ninth Day of Christmas is given to the Feast of St. Genevieve, who is sacred to Paris, where she lived in the fifth century as a nun. She saved the city from an attack by Attila and his Huns in 451. This she did through fasting and prayer, encouraging the residents of the city to join her. And around 475, she founded Saint-Denys de la Chapelle in Paris, which stands today as part of the Basilica of St. Denis.

There are no particular customs associated with the Feast Day of St. Genevieve, nor this Ninth Day of Christmas (as well as the day that follows) and my theory is that this more contemplative time within the Christmas revels is here by design. We need some time for quiet and for reflection, and the most proper way to celebrate this Ninth Day of Christmas, I think, is with stillness and candlelight. St. Genevieve is another of the midwinter saints typically associated with light: she is often seen holding a candle, and the story goes that the devil time and again would blow out her candle as she went to pray at night, so as to thwart her. Genevieve, however, was able to relight her candle without need of flint or fire. And so she is another of the light bearers in midwinter’s darkness. Thirteen days on the other side of the solstice, already light is increasing as we begin the journey toward summer’s warmth once more in the Northern Hemisphere. The light of St. Genevieve promises to never be snuffed by the darkness.

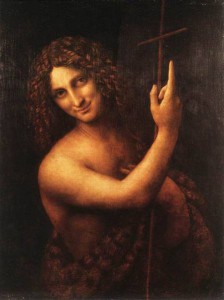

Image: St. Genevieve by an unknown artist, 17th century. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.