The Civil War effectively ended with the surrender of Robert E. Lee to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomatox Courthouse in Virginia on April 9, 1865, is a fact we’re taught in American History classes. But things were not magically resolved that day, and it took a while for Union forces to take control of all the states that had been in rebellion. It was not until the 18th of June that Union troops arrived on Galveston Island to bring the State of Texas back into the fold, and the next day, June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger read a proclamation from a Galveston balcony:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

This proclamation is at the heart of Juneteenth. Newly emancipated slaves rejoiced right there in the streets of Galveston. It took a few years before that proclamation made its way across the vast State of Texas, and, of course, the news was not always welcome: newly freed slaves were often the targets of violence. Still, by the year that followed that original proclamation in Galveston, Juneteenth celebrations were sprouting up all over Texas and continued spreading, mostly among African American communities, throughout the country. As the years went on, and with the new challenges of Jim Crow and segregation, Juneteenth became a day to gather family, to reassure each other against adversity and challenge. In fact, Emancipation Park in Houston is a fine example of Juneteenth spirit challenging Jim Crow laws: When whites kept blacks from using public spaces, those who wanted to celebrate Juneteenth properly gathered the money necessary to purchase a site of their own, and Emancipation Park is one such site.

Linguistically, the name Juneteenth, which is such a wonderful word, is a portmanteau (itself a wonderful word) of the words June and nineteenth. The day is also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day. Folks early on wore their finest clothes for Juneteenth parades and gathered to eat good food, with barbecue always prominent on the Juneteenth menu. Nowadays the dress is less formal but the celebration endures. The day often showcases the importance of the contributions of black Americans and African American culture. But even now, after all these years, Juneteenth is a day to celebrate hard-earned freedoms. We should never become complacent about these things.

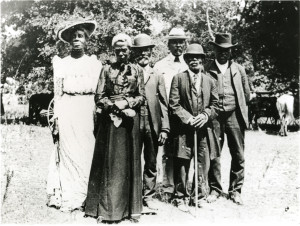

Image: A photograph taken at an early Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas.

Always a wealth of knowledge to learn at Convivio:-) Thanks John.