It’s Valentine’s Day and it’s also the first day of Lent. That’s one of the dangers of a February holiday like Valentine’s Day: sometimes it falls on a fasting day. A really nice dinner is a traditional part of many Valentine’s Day celebrations; sometimes, like this year, Lent shows up as an unwelcome guest at the table. Whether you fast or not is up to you. I certainly won’t say anything.

Nonetheless, with the passing of Fat Tuesday, the excess of Carnival is done. It’s now Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent, a forty day journey of penitence, fasting, and almsgiving. The idea of abstaining from meat and things of the flesh (milk, cheese, eggs) during Lent was instituted by Pope Gregory in the late 6th century as a way of helping his flock prepare for Easter and the miracle of spring by mirroring Jesus’s forty days of fasting in the desert. But although it is a season of denial imposed by religious belief, the fact is that in earlier times this was a season of scarcity in general. Folks did their best each fall during harvest time to store away food and provisions to last through the winter, but by this time of year, these things were beginning to get scarce. The salted meat would be running low, the eggs running out. There’s not much to gather in the wild and not much is growing yet in the fields. In the Northern Hemisphere, we are just beginning at this point to spring out of winter. In times past, if you were lucky, you’d still have a decent quantity of flour in the barrel and a good store of dried beans, root vegetables, and dried fruits and nuts and hopefully some salted fish. Even without a decree from the Pope, some fasting would almost always be necessary to get your family through the remaining weeks of winter.

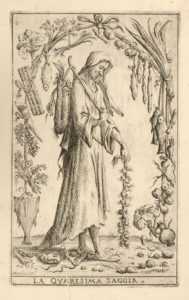

As I mentioned in the Book of Days chapter two days ago, titled “Fat Tuesday,” the traditional symbol of Carnevale in Italy is a plump man wearing a necklace of sausages about his neck. He is in stark contrast to the traditional symbol of Lent: a gaunt old woman, all skin and bones. She is known as La Vecchia. Her time gets the name Quaresima, which sounds so much more lovely than our stark English word Lent. Sometimes La Vecchia takes the form of a baked loaf of bread in the shape of a skinny old woman with seven legs. One leg is broken off with each passing Sunday of Lent, a calendar of sorts, marking the passage of this spare season.

Nowadays, most Catholics simply abstain from meat on Fridays during Lent. Restrictions have loosened a lot over the years, perhaps in direct proportion with our abilities to keep food on the table at all times of the year. The restrictions are mostly now just symbolic. But the custom we have of dyeing eggs at Easter comes directly out of the old ways of Lent: folks were so excited to welcome eggs back into their daily diet each spring, they celebrated by dyeing them with natural dyes like beetroot, chamomile flowers, red cabbage, and onion skins. I still like dyeing eggs with these things of nature.

Being a time of spare solemness, it is not surprising that there are not many celebratory foods that accompany Lent. There is one, however: The humble pretzel. At their most basic, pretzels are made with just three ingredients, all Lenten-friendly: flour, salt, and water. It is thought that the name “pretzel” is derived from the Latin bracellae: “little arms,” essentially, evoking the prayer posture of early Christians, who prayed with their arms crossed over the chest. Go ahead, try it right now, then look down at your chest: classic pretzel shape. This penitential bread––again, so common nowadays so as to be nothing special––has a history that goes back many many centuries. The first pretzels were thought to be made in the 6th century. Some historians think they go back three centuries more.

Connexions like these are, I think, so fascinating. That a common pretzel can have such interesting roots (and deep ones, at that) and mark our celebratory days (or penitential ones, in this case) is such a wonderful thing.

Love is at the heart of our table no matter the meal or the season, even in the humble dishes that make up our meals during Lent. Perhaps there is no better Valentine’s Day than one that falls on Ash Wednesday, when we are reminded that we are made from the earth and to earth we shall return. The time is short. Ash Wednesday is, at its core, a day to remember the brevity of things and to understand that we are here to love and to lift each other up. These forty days of Lent are a good time, I feel, to focus not on what we deprive ourselves, but on what we can do to enrich the lives of others. So go on: Love with all your might.

Image: “La Quaresima Saggia” by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli. Engraving, c.17th century. The haggard old woman of Lent, trodding upon the remnants of Carnevale, framed by the foods of her season: fish and snails, onions and other root crops, beans, and I’m pretty sure those are cardoon stalks at the top right.

Thank you, John.

That was really interesting! Thank you for sharing.

Interesting, as always. Thank you, John.

Great piece, John. So, let’s imagine the dilemma of the church pastor with Ash Wednesday falling on Valentine’s Day — excessive gifting and celebration versus the beginning of fasting and deprivation. Solution? Pink ashes. (Or better yet, the imposition of ashes in the shape of a heart).