It’s a mid-week in mid-February and here come a couple of multi-faceted, multi-ceremonial days. It’s Tuesday today to begin with, and an extraordinary one at that: It is Mardi Gras in New Orleans and Mobile and Key West, and in Venezia, it is Martedi Grasso, and both the French and the Italian translate to Fat Tuesday. This is a movable celebration based on the timing of Lent, which is based on the timing of Easter, which is based on the timing of the full moon that comes with or after the Vernal Equinox. Tonight, the festivity of Carnival concludes. But for most of us, those of us who are far from the cities that celebrate Mardi Gras, tonight is simply a time to eat pancakes or crepes for supper, for the day is also known as Pancake Tuesday, and Shrove Tuesday.

Shrove Tuesday concludes Shrovetide, which is the time we’ve been in for several weeks now: the time after Christmas ends and before Lent begins, and there are many traditional foodways for Shrove Tuesday, even beyond the delectable pancake. Polish bakeries will have pączki today, a rich filled doughnut, and Germans will be making doughnuts, too, for this night they call Fasnacht: this night (nacht) before the fast. And in Sweden and Finland, you’ll find semlor on the table: buns scented with cardamom and filled with almond paste and cream. Our friends at Johan’s Joe, the Swedish coffeehouse in West Palm Beach where Seth and I have been known to buy a semla or two, tell us that originally semlor were made only for Fat Tuesday, or Fettisdagen, but nowadays Swedes bake semlor for all the Tuesdays of Lent. Traditions are living things; they do evolve.

How celebratory for a Tuesday to have pancakes for supper! But no matter if you are eating pancakes tonight, or doughnuts, or semlor, the idea behind all these things is the same. To clear the larder of the things that, traditionally, were not to be consumed during the Lenten fast, and in years past, this was a fairly extensive list (much more so than it is today): no eggs, no meat, no lard, no milk, no cheese, no sugar… no nothin’. And it was not just on Fridays; it was for the full forty days of Lent. When our ancestors fasted for Lent, they really meant it. Lent was forty days of beans and pulses and vegetables and fish and absolutely nothing fun. The Italians certainly understood this. Their traditional symbol for Carnival was a jolly plump fellow called il Carnevale Pazzo: Crazy Carnival. He’s usually seen dancing and playing a mandolin while a necklace of sausages dangles around his neck. But Lent brings la Quaresima Saggia: Wise Lent. She is thin and gaunt and somber. Head cast down, pensive, she is dressed in rags and carries a rope of garlic and dried cod.

It is il Carnevale Pazzo who tucks us into bed tonight on Shrove Tuesday, and in the morning, la Quaresima Saggia is the one who wakes us up, and when she does, we awaken to Ash Wednesday, the first day of our 40-day Lenten journey. Lent these days, it must be said, is no big sacrifice. Some folks give up sweets for Lent, or give up booze, or give up gossiping. All the Church asks is that we be more prayerful and more penitent and give up meat on Fridays. As a kid, for me this meant a season of fish sticks for supper on Fridays, or lentil soup without the sausage. Which was all fine with me. I was the sort of kid who ate anything that was put on my plate, no questions asked. Lucky for me, though, I was born in an age where fish sticks on Fridays met the obligatory sacrifice for Lent, and no one took away my eggs and cheeses and desserts. That would be a real sacrifice.

And then sometimes, like this year, St. Valentine runs headlong into la Quaresima Saggia, and therein lies a dilemma for young lovers who find themselves seated at fancy restaurants for an amorous Valentine’s Day dinner, debating whether they should have the fish or the lentil soup… or the Boeuf Bourguignon cooked to perfection. We may find ourselves sitting there, wondering WWJD (What Would Julia (Child) Do?).

I am not “old” but I am older, and Seth and I have more sense than to dine out on Valentine’s Day. One of our favorite Valentine’s Day celebrations was take out Thai noodles, picnic-style on a blanket on the floor, while we watched A Room with a View on DVD. This year, our niece is coming to dinner and she doesn’t eat meat, anyway. She won’t even realize it’s a ceremonial night of sacrifice when I put a bowl of Pasta Fagioli in front of her. It is an experiment, mind you: She’s not terribly adventurous when it comes to food, and this will be her first encounter ever, I am told, with the mild yet delectable cannellini bean. My hope is she will love cannellini beans and my version of Pasta Fagioli––cavatappi with those creamy white beans, infused with garlic and drizzled with fresh olive oil, seasoned just right with freshly-ground salt and pepper. Where love takes root, we say, let it grow. Especially on Valentine’s Day (and especially one combined with Ash Wednesday).

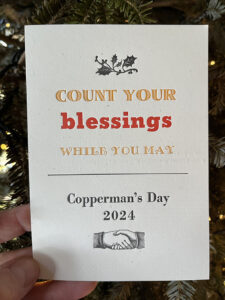

ONLINE SPECIALS: A COPPERMAN’S DAY SPECIAL, PLUS A VALENTINE SALE!

You’ll find our newest Copperman’s Day print and all our Copperman’s Day prints now at our our online catalog when you CLICK HERE. Order 5 or more of any of our mini prints (Copperman’s Day prints, B Mine Valentines, and our famous Keep Lake Worth Quirky prints) and use the code COPPERMAN when you check out; we’ll take $5 off your order to help balance out our flat rate domestic shipping charge of $9.50. (And if you ordered Copperman’s Day prints last week, when we were first announced them, worry not! Your orders should ship out tomorrow.)

If you’re doing more serious shopping (and we do have lots to offer if you are), you may instead use discount code LOVEHANDMADE to save $10 on your $85 purchase, plus get free domestic shipping, too. That’s a total savings of $19.50. Spend less than $85 and our flat rate shipping fee of $9.50 applies. Newest arrivals: Letterpress printed Valentine cards in the Valentine section, and check our Specialty Foods section for some incredibly delicious chocolate we found from Iceland, including a particularly Icelandic blend of milk chocolate and licorice. If you love both these things, well… Icelanders long ago discovered that covering black licorice in milk chocolate, then dusting the result in licorice powder, is just amazing. (Trust me: we’re on our third bag so far.) CLICK HERE to shop; you know we appreciate your support immensely.

Image: “The Pancake Bakery” by Peter Aertsen. Oil on Panel, 1560. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons.