There was a time when folks would be off from the major part of their labors for all of the Twelve Days of Christmas. When they went back to work once Christmas had passed, it was not without some fun and ceremony. For the women, it was traditionally the 7th of January; for the men, it was whichever Monday happened to follow Epiphany. Every now and then, both would fall on the same day, as is the case this year… and so we step out of the Christmas season today and back into ordinary time with two traditional English holidays known as St. Distaff’s Day and Plough Monday. It also happens to be an important day for printers like me: Copperman’s Day; more on that later. First, St. Distaff and the Ploughboys (which I’m going to add to my list of good potential band names).

ST. DISTAFF’S DAY

January 7

The English have a long history of creating saints’ days for saints that never existed at all. St. Monday was the name given to the long weekends sometimes taken by shoemakers, and St. Tibb was often used as a metaphor for never, as in, “Hey, I lent you a shilling last week; when will I get my money back?” “Worry not, I’ll be sure to have it back to you by St. Tibb’s Day.” Which is all well and good until the lender realizes that there is no St. Tibb’s Day. Neither St. Tibb nor St. Monday ever existed, and nor did St. Distaff. The distaff, however, was a central tool to what was considered in those days “Women’s Work”: the spinning of wool or flax to make fiber for weaving into cloth. The distaff and spindle were the tools that preceded the spinning wheel, and rare it would have been to find a woman who knew not how to use them. We get the word spinster from this, which was once was a recognized legal term in England to describe an unmarried woman, and the terms spear side and distaff side were also legal terms to distinguish the inheritances of male from female children. It was on St. Distaff’s Day, the 7th of January, that women traditionally returned to their spinning. Meanwhile, the men were still underfoot in the house. Their job on St. Distaff’s Day was one of mischief, with the goal usually being to set fire to the flax the women were spinning. The women were wise to this custom, though, and typically kept several buckets of water nearby. Very often, it was the men who got the worst of it: to have a bucket of water dumped on you in the cold of January… for sure, St. Distaff’s Day lent a bit of excitement to the idea of returning to ordinary time. On years like this one, however, when both St. Distaff’s Day and Plough Monday fall on the same day, the men had customs of their own to attend to.

PLOUGH MONDAY

First Monday after Epiphany

The men got a moveable date for their traditional Back to Work day. It’s a holiday that is noted as far back as 15th century pre-Reformation England as a religious festival in which money would be raised for the parish. Plough lights would be illuminated in the churches as a way of blessing the local farmers and their fields and crops. The parish was often the home of a community plough, as well, for farmers who could not afford their own. When the Church of England broke away from Rome, this was one of many practices that were deemed “popish” and left behind, but by the late 1700s, Plough Monday began seeing a revival, and a distinct shift from its origins. In its newer incarnation, there was a lot more ale involved. There would be a ceremonial ploughing of the ground, which very often, in days of dirt roads, would be in the very road that ran through the village. The ploughs would be blessed and finely decorated, the men would parade in costume, there would be music and mummers and plays and a great hoopla of noise and all kinds of good sport. There would be a collection taken up door to door to pay for the tavern bill that came after; those who were too stingy to contribute risked having the path to their door ploughed, as well. Best, then, to contribute a few pennies to their sport.

As for the men’s costumes, the sillier, the better, and for sure there is a bit of the Feast of Fools, which we saw during the Twelve Days of Christmas, that comes into play on Plough Monday. It is traditional for one man in each Plough Monday gathering to dress as the Bessy, an old woman who we can link firmly to pagan goddess celebrations: she is the personification of the hag, the old woman of winter who, in the seasonal round of the year, will transform come spring into the virginal young goddess. And spring is not that far away in this world of spiraling circular tradition: Come February 2, we are halfway between Midwinter Solstice and Spring Equinox, a day marked by the holidays Candlemas, Imbolc, and Groundhog Day. It is a day seen in the traditional reckoning of time as spring’s first stirrings, even if winter still holds a strong grip. Though it still be cold, the sun is gaining strength by then, with considerably more daylight on the 2nd of February than there was on the 21st of December.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, this same Monday after Epiphany was an important day in the printing trade. It was known as Copperman’s Day.

COPPERMAN’S DAY

First Monday after Epiphany

The young Dutch printshop apprentices would be given the day off on this First Monday after Epiphany so they could work on a project of their own and show off the skills they’d learnt from the master printers. Copperman’s Day prints were typically small keepsakes sold for a copper apiece.

Seth Thompson and I have been printing Copperman’s Day prints from handset metal and wood types here at our Lake Worth print shop since 2014. Our first three were inspired by a Christmas Eve letter written by Fra Giovanni Giocando in 1513. In his letter, Fra Giovanni implores us to “take joy, take peace, take heaven.” The following year’s print featured an old toast, “Wes Hel,” inspired by Christmastide. That was the year my father had suddenly taken ill, and Wes Hel, the source of the later Wassail, means “Good Health.” We never did get around to announcing last year’s print, and it suddenly seems a bit late at this late hour as I write this to add it to the online catalog. As for this year’s print, what will it be? Ah, well, we’ll leave both last year’s and this year’s as secrets for now, secrets that I’ll reveal perhaps in the next Convivio Book of Days post, or certainly soon after.

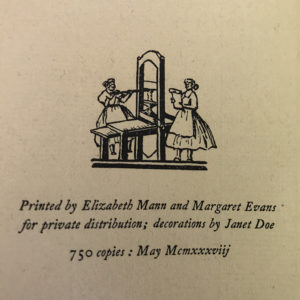

All of the images in today’s chapter, including those below, are taken from a small paperbound chapbook titled St. Distaff’s Day, printed letterpress by Elizabeth Mann and Margaret Evans of the Froben Press in 1938. The lovely illustrations are all by Janet Doe; the one that opens this chapter is of a distaff. I love the illustration of Mann and Evans at the handpress, with all the skirts and aprons. I’m often printing in just a pair of shorts. Times have changed.

No St Distaff? This is sad news for us handspinners, but I love the idea of there being a saint for spinners. Though I don’t always visit the blog, I do love reading when I do. So many reasons to celebrate ordinary stuff.

Well, Velma, no St. Distaff in terms of an actual historical figure… but certainly in terms of a celebratory day. Even Robert Herrick wrote about St. Distaff’s Day in 1648, so worry not: that must lend the saint some measure of authenticity:

Partly worke and partly play

Ye must on St. Distaff’s Day:

From the Plough soone free your team;

Then come home and fother them.

If the Maides a-spinning goe,

Burne the flax, and fire the tow:

Scorch their plackets, but beware

That ye singe no maiden-haire.

Let the maides bewash the men.

Give St. Distaff all the right,

Then bid Christmas sport good night;

And next morrow, every one

To his owne vocation.

Thanks for enjoying the blog, Velma!

Thank you for this post, John. May you and Seth take joy, take peace, take heaven in the new year.

Thank you, Marjorie. All good wishes for you and yours, too, this new year!

Lovely telling of historical rituals often needed today. Thanks.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Leonard! Happy Copperman’s Day.

This was a delightful read. Thank you for sharing this piece of history and tradition.

It’s my pleasure, Sue; it’s what I do. Thanks for reading!

Many of these imaginary saints arise because many Germanic languages distinguish between “saint” for a person and “holy” for a thing, but most Latin languages do not. The classic example is the incarnation of “holy wisdom” as “Saint Sophia”. Could an early “holy distaff” have been similarly incarnated?

Fascinating! Thank you, Henry! Great insight.

Lovely annd informative, as always. The ending, referring to the ladies printing in long skirts and pouffy sleeves, reminded me of the times I worked on the SP 40, wearing pretty dresses instead of jeans and tees, working on ‘A Visit to Cross Creek.’

Thank you, Paula. It does make me feel like perhaps I should wear a nice shirt and bow tie (and an apron) when I get to my Copperman’s Day print! Alas, I was out cold all day on Copperman’s Day with a terrible cold. Just starting to get better now.

Velma, fear not, handspinners have no less than four patron saints: Parasceva, Seraphina, Nicholas of Myra (aka Santa Claus) and Catherine of Alexandria. The last is the most prestigious, but has lots of other crafts and interests to look after. I’d go for St Nick!

AB is right, Velma; spinners (and most occupations) are covered by more than one saint. At least one is bound to have been a real historical person.

Wonderful piece, John. Happy New Year!

Thanks, Carol; happy new year to you, too!

What fun! Thank you so much for taking the time to research these holiday’s origins and then passing on the fun to us! I must confess I am very curious to know the content of Henry Kent’s address to the book-making women. Is this occasion in Britain or the USA? Thanks again for your time and diligence.

Hey Retta (you have the same name as one of my cousins, and there are many Mariettas in my family). I did research and was surprised to find that there is little record of this chapbook, even though 750 were printed and bound. Certainly we are the poorer for this.

I’ve thought about transcribing it here for you, but though it is a short text, it feels a bit long for transcribing today when I’m not feeling so well. Maybe I’ll just photograph all the pages and post them as a new chapter of the Convivio Book of Days. Either way: It will be done!

Also, I’m guessing the address and the press were both in the US.