Bartlemas approaches. That’s another name for St. Bartholomew’s Day, which falls on the 24th of August each year. His feast day is celebrated not so much in churches as it is amongst practitioners of the Book Arts. St. Bartholomew is a patron saint of bookbinders, but his day is just as important to the other two branches of our craft: papermaking and printing––the one sometimes called the Black Art. St. Bartholomew’s Day brings the Bartlemas Wayzgoose, a particularly English celebration that comes out of the shifting of the seasons––the recognition that summer is waning.

Not much is known about St. Bartholomew himself. He was one of the Twelve Disciples. He is thought to have traveled to India, but tradition says that he met his end in Armenia in the first century. His martyrdom was a gruesome one––one that by association made St. Bartholomew a patron saint of butchers (a common trade amongst my paternal ancestors) and of tanners and of bookbinders, who very often bind books in leather. I’ll leave the method of his martyrdom, based on those associations, to your imagination, but early bookbinders found it a worthy connexion, hence his patronage of their craft.

For papermakers, the connexion goes back to the days before glazed glass windows. Back then, it was waxed paper that was used to keep out the elements, and the arrival of Bartlemas was the signal that it was time to paper the windows in preparation for winter. Once this St. Bart’s window paper was made, the papermakers went back to making paper for the printers, clearing out the vats and recharging them with new pulp made from rags that had been retting all summer long.

But trust me: it’s the printers who really know how to celebrate St. Bartholomew’s Day. Bartlemas, being a full eight weeks past the summer solstice, brings with it each year a certain reality: Sunlight, like summer, is waning, and the days are growing darker and darker. Along with the papering of the windows at Bartlemas came the necessity of illuminating the print shop with lanterns and candles. A good print shop proprietor would make a celebration of the day. Randall Holme, in 1688, gave us this description of the Bartlemas Wayzgoose: “It is customary for all journeymen to make every year, new paper windows about Bartholomew-tide, at which time the master printer makes them a feast called a Wayzgoose, to which is invited the corrector, founder, smith, ink-maker, &c. who all open their purses and give to the workmen to spend in the tavern or ale-house after the feast. From which time they begin to work by candle light.”

To be sure, there was a good quantity of ale consumed as part of the Wayzgoose. In some places, mead, the delightful intoxicating beverage made from honey, was the beverage of choice. Especially in Cornwall, where a Blessing of the Mead ceremony takes place even today at this time of year. Continuing the road of connexions, our friend St. Bartholomew is also a patron saint of beekeepers, and as we continue to gather our stores for the coming winter, it is traditional, too, to bring in the honey crop on his feast day.

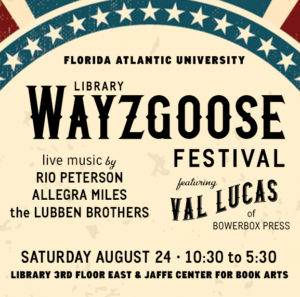

If you’re here in South Florida, I hope this Saturday you’ll join us at our local Wayzgoose: It’s Florida Atlantic University’s Library Wayzgoose Festival in Boca Raton, happening from 10:30 to 5:30 at the Jaffe Center for Book Arts and throughout the 3rd Floor East of FAU’s Wimberly Library, which is the Jaffe’s home base. There will be print demos all day with Val Lucas of Bowerbox Press, live music all day, and the Wayzgoose Makers Marketplace (we’ll be there offering some of our wares as well as pottery by Seth’s Royal River Pottery company). You’ll also get to make your own paper printer’s cap, participate in telegraph demos and an exquisite corpse story project, play corn hole, and there are two gallery talks through the day, and a White Elephant Sale, and there will be artisan breads for sale (baked and donated by Louie Bossi’s) and amazing doughnuts for sale, too (we’re donating the doughnuts, but we’re not making them!). If it all sounds like a pretty wonderful day, I’d say you were right. So please come!

Finally, here’s another bit of Bartlemas Wayzgoose lore that I love, something I’ve mentioned before, but still have not been able to find further information on. Be that as it may, it was on August 27, 2010, that the Jerusalem Post reported that Johannes Gutenberg’s 42-Line Bible, the first book printed from moveable type, was completed on St. Bartholomew’s Day in 1454. Some claim, too, that that first printed book explains why printing has a history of being called the Black Art. They say that Johannes Fust, Gutenberg’s business partner, sold several of the printed bibles in France without explaining how they were made. When it was discovered that the books were identical copies of each other, Fust was accused of witchcraft and was briefly imprisoned for that crime. It was a different world back then, with information spread by rumors. It was the printing press, though, that ushered in an age of knowledge and literacy and enlightenment. Some would say, too, that we have reverted back to those medieval ways: there are those who claim time and time again that the printed word is not to be trusted, calling trusted information sources “fake news,” feeding us their own brand of misinformation through social media, which, when you get right down to it, is just the 21st century equivalent of medieval rumor. 565 years after Gutenberg, we find ourselves again no wiser than Johannes Fust’s accusers.

One thing is certain: if you are a book artist or if you are a book enthusiast, St. Bartholomew’s Day is a very auspicious day for you. For this Bartlemas Wayzgoose, then, certainly we have cause to celebrate books and the people who make them: the papermakers, the printers, the bookbinders, the book artists. This Bartlemas, let us raise our glasses to St. Bart and to all of these good artisans… and to celebrate the printed word and make a pledge to value its importance to good living and to good citizenship. The Black Art might just be more important than we think.

If you’re coming to our local Wayzgoose, just look for the blue and white MAKERS MARKETPLACE signs that will be posted on FAU campus roads. See you there… I’ll be wearing a paper printer’s cap. Here’s a link to the Facebook invitation, too. (I’m not on Facebook for the news; just for the events!)