FOURTH DAY of CHRISTMAS:

The Feast of Fools

Tradition calls for the ceremonial reversal today of the normal order of things. Here we have a Christmas custom that is rarely practiced today (though perhaps should be) and one that is definitely pagan in nature, this is a custom that goes back much further than the birth of Christ. It goes back to the feast that is probably at the heart of most of our Christmas customs: the Roman Saturnalia, a winter solstice celebration that predates Christmas by many centuries and that spread throughout Europe with the Roman empire. A big part of Saturnalia was the abandonment of the rules that the Romans loved so dearly. It was a time for disguises and games and in that ceremonial reversal of the normal order, slaves were waited upon by their masters, mock kings were crowned, and general chaos ruled the land.

Old habits die hard. As Rome became Christianized, celebrations that proved difficult for the Church to subvert just became Christianized and so the birth of Christ was assigned to the winter solstice and Saturnalia, with all of its festivity and gift-giving, became Christmas. The chaos of Saturnalia became the Feast of Fools, and it continued on with great conviviality through the medieval period, which was, perhaps, its heyday.

It was the Lord of Misrule who was elected to reign over the Christmas revelry. Much like the election of the Boy Bishop that we discussed in yesterday’s chapter of the Book of Days, the Lord of Misrule was usually someone who would not typically be in a position of power. He might be a servant in ordinary time, but now, during Christmastide, he was lord of the revelry and he reigned without fear of retribution. His charge, actually, was to act as foolishly as possible. The Lord of Misrule reigns until Twelfth Night, as Christmas comes to a close.

Not much of this aspect of Christmas survives today. We are not a people given to chaos, when you get right down to it. We like order and routine. Some remnants you might find from the Feast of Fools, however, are the mummer’s plays and morris dancers that make their rounds in villages at this time of year. The mummer’s plays and morris dancers are mostly an English phenomenon, but mummer’s plays are also popular in Philadelphia at the new year. The mummers and morris dancers, guised in ribbons and bells and strange costumes, are direct descendants of the Lord of Misrule. The practice of baking a coin in a pudding or a charm in a cake also harkens back to these ancient celebrations. It was often the person who found a coin in his pudding who was elected lord of the revels.

So from whence comes all this chaos? One of the most beautiful things about the Twelve Days of Christmas is a mathematical thing: Half of those twelve days fall in the old year, half in the new. The old year is dying, disintegrating into chaos. Out of that chaos is born the new year, and order returns along with the return to ordinary time after Christmas. That is rich and potent symbolism. The Romans understood this, our medieval ancestors understood this.

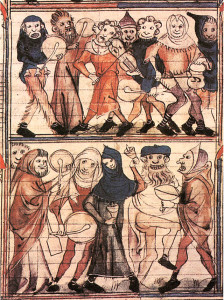

Image: A miniature illumination from a French fourteenth century book depicting a Fête de Fous (Feast of Fools) scene.