The nights grow longer and darker on our approach to the solstice of Midwinter, and in these final few weeks of night expanding, the first of the midwinter gift bearers, magical beings that they are, begin their journeys in the lands where they are known and loved. The first of them comes tonight, for tomorrow is St. Nicholas’ Day, and in these overnight hours, on its eve, the old Bishop of Myra makes his way through places like Germany and the Netherlands, Austria and Northern Italy. I’m afraid that by the time most of you read this, it will already be the Sixth of December, St. Nicholas’ Day, and you may be left wondering how your shoes came to be filled with nuts and sweets and other small presents overnight. Well, now you know. (Book of Days subscribers: I apologize for my belatedness; ’tis a busy time of year for your Convivio Bookworks guys.)

This St. Nick is an older version of the jolly fellow we know so well here in the States. The Old World version is not so portly, and he wears the long robes and miter of a bishop, for St. Nicholas was the Bishop of Myra in the fourth century. He was known in that distant land for bestowing gifts upon those who most needed them. As a saint, the Dutch sailors implored his protection during storms as they sailed the high seas, and he is a patron saint of Bari, the Italian homeland of my father’s family.

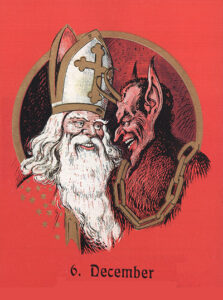

If you awake on the Sixth to find small gifts in your shoes but also scratching your head, wondering what was up with those bad dreams you had, this may have to do with the presence of St. Nicholas’ dark companion. The companion goes by many names, depending on the region––Knecht Ruprecht, Black Peter, Pelznickel… but he is best known as Krampus: half man, half goat, horned and furry, with an astonishingly long tongue. St. Nicholas concerns himself with the good children. Krampus deals with the naughty ones. Krampus carries chains or birch switches and oftentimes a sack, in which he gathers up the bad children who deserve nothing more than to be carried away. It’s a bit terrifying, but also good fun––especially in the Krampusnacht parades that feature both St. Nicholas and Krampus.

Our local Krampusnacht will take place a bit belatedly (you may be spotting a pattern, though I have nothing to do with the belated date of this one): the American German Club in suburban Lake Worth will be hosting its inaugural Krampusnacht celebration this Friday from 7 to 11 PM. We’ll be there that night and all the weekend that follows with our largest ever pop-up shop, and you can shop our traditional artisan goods for Christmas and everyday, too (including Millie’s Tea Towels), as the somewhat scary Krampusnacht on Friday night evolves into the lovely Christkindlmarkt Saturday and Sunday. Tickets are required, and I’ve just found out that Christkindlmarkt tickets are already sold out, but Krampusnacht tickets are still be available (click here). The folks at the club are telling us that this Krampusnacht is for the adults, not the kids. Take that to mean whatever you’d like. Krampusnacht and Christkindlmarkt are most likely our last public pop-up events for this Yuletide season before Seth and I, too, shift into resting a bit and making our own house as fair as we are able for Christmastime.

St. Nicholas may be the first of the midwinter gift bearers, but there is a long line of others to come over the course of these long dark nights, all depending on the lands in which you live. He and Krampus will be followed over the next few weeks by the Christkindl in Germany, by Sankta Lucia in Sweden, by Father Christmas and Santa Claus, by los Tres Reyes (the Three Kings) in Latin America, and a kind old witch named Befana who travels through Italy sweeping away the remnants of the Christmas season in early January. Ah, but that is far away or long ago, depending on your perspective, and for now, we wish you all good things this St. Nicholas’ Eve. May Krampus keep his distance. Sweet dreams!

CHRISTMAS STOCK-UP SALE

For those of you not around here (or who don’t want to be scared by furry goat creatures on Friday night), there’s the Convivio Bookworks Christmas Stock-Up Sale. Spend $75 on anything and everything in our catalog, and save $10 plus get free domestic shipping: a total savings of $19.50. Just use discount code STREETFAIR at checkout. Click here to shop! We always offer free domestic shipping when you spend $60 –– no discount code is required for that. I think you’ll be amazed at all you’ll find that’s new at our website, especially if you haven’t visited in a while! Locals, you can choose Free Local Delivery at checkout no matter how much you spend… I’ll deliver on my vintage Raleigh bicycle in the 33460 zip code.

Image: “Nikolaus und Krampus,” from a vintage penny postcard produced in Austria, circa early 20th century. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. These two seem pretty happy to be pals. Darkness & Light?